The news that Intel’s Galileo is on its way just underlines to me how the chip giant has lost its way.

The news that Intel’s Galileo is on its way just underlines to me how the chip giant has lost its way.

The “open source” computer costs $70, and uses its Quark microprocessor. Intel clearly thinks it will compete against the highly successful Raspberry Pi but clearly it hasn’t got a chance to play catch up.

The launch mirrors Intel’s late attempt to climb on the tablet bandwagon by cutting the price of its Atom microprocessor to compete with ARM and Nvidia based chips. But it hasn’t got an earthly here, either. Manufacturers are very chary about using anything with the Intel name associated with the tin. Again, that’s underlined by vendors’ reluctance to be associated with Intel.

Cheap is everything in the tablet market now and even though Intel’s chips might be, er, cheap as chips, the economics of this don’t really make a lot of sense to anyone. Sure, Intel has heaps of capacity but that in itself is part of the problem. State of the art fabs are really expensive these days and the volume game just doesn’t fit Intel’s business model.

In reality, the chip giant really has very little new to say. The new broom in the shape of CEO Brian Kzanic appears to be attempting the Herculean task of cleaning the Augean Stables not just of the dung but also of a heap of very good people who have let their legs do the walking.

Datacentre business no doubt is still healthy for Chipzilla, but on the other hand independent market research shows that the notebook market is on the wane. Sure, enterprises will refresh their notebooks but with the arrival of BYOD, there’s a level of ambiguity which must leave Intel more than a little bemused.

In truth, Intel has had zilch to say in the last three years as smartphones and tablets transformed the “traditional” Wintel model.

As part of the antitrust agreement following the demise of DEC, Intel found itself with StrongARM devices. At the time, we asked top executives from the firm why it didn’t just cut the Gordian Knot and produce a highly portable ARM based device? The answer, of course, was that Intel was on the Centrino notebook gravy train. Sean Maloney, now a non-executive director at Chinese foundry SMIC, realised that the Atom chip might well cannibalise the notebook market but nobody at Intel appeared to have looked further than the next three quarters and see its dominance becoming more and more eroded.

Of course, Intel has oodles of cash in the bank but oodles don’t last forever. Re-engineering its business model is, for Intel, a far from trivial task. As an Intel watcher for the last 30 years, I will be most interested to see what happens in the next 12 to 18 months.

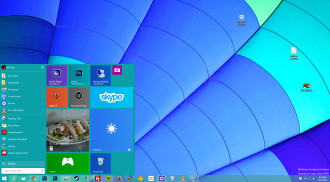

We’ve already written how Microsoft is to give away Windows 10 to Chinese users but senior VP Terry Myers has revealed other elements that he hopes will give his company an edge on the operating systems front.

We’ve already written how Microsoft is to give away Windows 10 to Chinese users but senior VP Terry Myers has revealed other elements that he hopes will give his company an edge on the operating systems front.